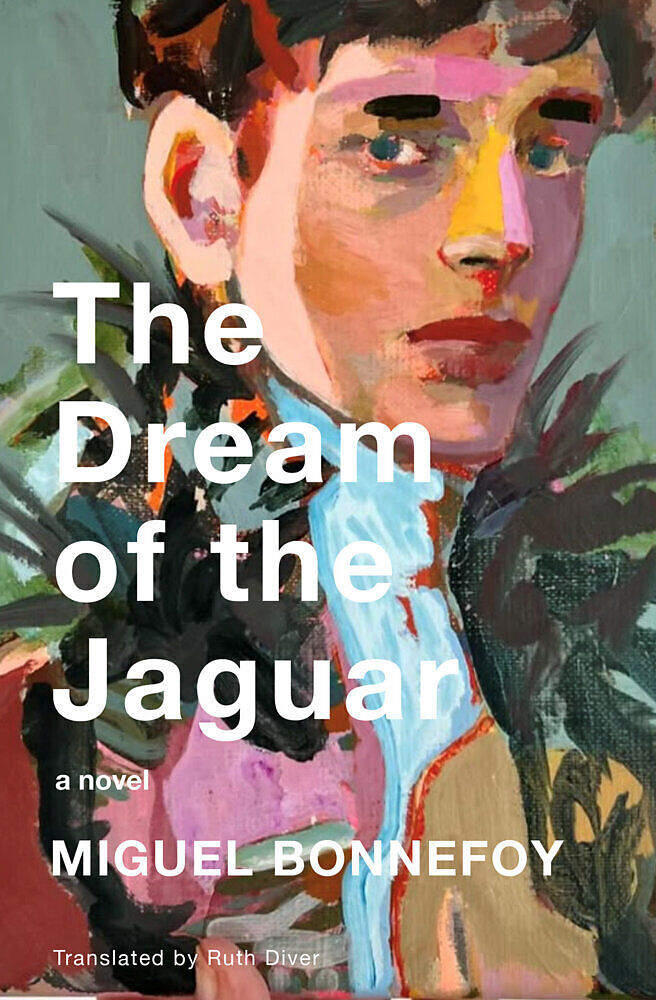

The Dream of the Jaguar

Beschreibung

An enchanting family saga in the vein of One Hundred Years of Solitude, this prize-winning novel illuminates Venezuela s history through the lives of its memorable characters. When a mute beggar from Maracaibo, Venezuela, takes in a newborn abandoned on the st...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 19.50

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

An enchanting family saga in the vein of One Hundred Years of Solitude, this prize-winning novel illuminates Venezuela s history through the lives of its memorable characters.

When a mute beggar from Maracaibo, Venezuela, takes in a newborn abandoned on the steps of a church, she has no idea of the extraordinary destiny that awaits the orphan. Raised in poverty, Antonio will be a cigarette seller, a porter on the docks, a servant in a brothel before becoming, thanks to his effusive energy, one of the most illustrious surgeons in his country.

An exceptional partner will inspire him. Ana Maria will distinguish herself as the first female doctor in the region. They will give birth to a daughter whom they will name after their own country: Venezuela. Connected to South America by her first name as much as by her origins, she only has eyes for Paris. But we never truly leave our own people. It is in the notebook of Cristóbal, the last link of their family, that the stories of this astonishing lineage will finally take shape.

In this vibrant saga full of unforgettable characters, Miguel Bonnefoy paints a picture, inspired by his own ancestors, of a remarkable family whose fate is intertwined with that of Venezuela.

Autorentext

Miguel Bonnefoy was born in France in 1986 to a Venezuelan mother and a Chilean father. His earlier novels, Octavio s Journey and Black Sugar, have sold more than thirty thousand copies each in France and have been translated into several languages. In 2013 Bonnefoy was awarded the Prix du Jeune Écrivain. His novel Heritage (Other Press, 2022) received widespread critical acclaim in France, including being short-listed for the Prix Femina, the Grand Prix de l Académie française, and the Goncourt Prize.

Ruth Diver holds a PhD in French and comparative literature from the University of Paris 8 and the University of Auckland, New Zealand. She won two 2018 French Voices Awards for her translations of Marx and the Doll by Maryam Madjidi, and Titus Did Not Love Berenice by Nathalie Azoulai. She also won Asymptote s 2016 Close Approximations fiction prize for her translation of extracts of Maraudes by Sophie Pujas.

Leseprobe

Antonio

On the third day of his life, Antonio Borjas Romero was abandoned on the steps of a church in a street that today bears his name. No one could be sure of the precise date on which he was found. All that is known is that every morning, a destitute woman would sit there, always in the same spot, put down a gourd bowl, and hold out her fragile hand to the passersby on the parvis. When she first set eyes on the infant, she pushed him away in disgust. But her attention was suddenly caught by a little shiny box hidden in the folds of his blanket, which someone had left with him as an offering: a tin rectangle, its silvery surface engraved with fine arabesques. It was a cigarette rolling machine. She filched it, put it into the pocket of her dress, then lost interest in the baby. But she noticed during the morning that the infant s timid wailing, his hesitant cries were so endearing to the churchgoers, who thought the two of them were together, that one by one they soon filled the bottom of her bowl with copper coins. When evening came, she took the baby to a farmyard, stuck his mouth to the teat of a black goat whose udder was covered in flies, and kneeled under its belly to make him suckle the thick warm milk. The next day, she wrapped him in a kitchen towel and hung him at her hip. After a week, she started saying that the child was hers.

This woman, whom everyone called Mute Teresa because she had a speech impediment, must have been somewhere in her forties, although she herself was incapable of giving her exact age. There was something Indian about her face, and on the left side, a slight paralysis caused by an ancient fit of jealousy. She carried nothing more than spongy skin on her bones, her hands were covered in sores that never healed, and her dirty white hair fell flat beside her face like the ears of a basset hound. She had lost the fingernail on her left thumb when a scorpion hiding in the back of a drawer had stung her hand one day. This did not kill her but formed a kind of sausage of flesh at the end of her thumb, a dead growth, and it was that flap that the child sucked before falling asleep during his first weeks.

She named him Antonio, for the church where she found him was placed under the patronage of Saint Anthony. She fed him with her own rage, with her silent pain. During his first few years, she had him lead a disorderly, shameful, indigent life. She convinced herself that if he should survive this misery, no one other than himself could kill him. At one year old, he could barely walk but could already beg. At two, he spoke sign language before he could speak Spanish. At three, he looked so much like her that she started wondering whether she had actually found him on the church steps, or might in fact have brought him into the world herself, in the backyard of a hovel, in the hollow of a hay bale, between a gray donkey and a lamb. She dressed him in filthy rags, and, to gain sympathy from the passersby, would hold him tight in fake tenderness, drenching him in acrid sweat that the heat turned into a kind of greasy yellow gelatin. She fed him goat cheese rolled by hand, slept with him in her shelter made of faded newspapers at the back of a makeshift sheep pen, and perhaps no woman ever showed so much courage in looking after a child she did not love.

Nevertheless, for Antonio, this lying, miserly, scurrilous, and thievish woman was the best possible mother to whom he could aspire. He took the roughness she showed him and the venomous love that poverty had woven between them to be tenderness. He grew up with her at La Rita, on the shores of Lake Maracaibo, in a place that was so dangerous that it was called Pela el Ojo, Keep your eyes peeled.

When Antonio turned six, he no longer believed in miracles but sold jet pebbles as lucky charms and knew how to read cards, for Mute Teresa was adamant that this was the only science that people could be convin